A short story

Lobengula’s Lover, set in the mid to late 1800s, is based on what is said to be a true story although I could find only two lines about it in an old book. I’ve used my imagination to retell it here. If anyone knows of a reliable source for the original tale, I’d be pleased to hear from them.

Lobengula was the last King of the Matabele people and was the son of Mzilikazi who led his people across the Limpopo to escape the feared Zulu king, Tshaka.

Lobengula’s Lover

I have not told Lobengula about the black mamba that I have seen three times now descending the great dome of rock above my dwelling. It slips fast as a flash flood down the erosion gully that scours the granite, its ash-grey length running effortlessly over the green peeling branches of the paper trees at the foot of the slope, limb entwined against limb, as if it would mate. Then it vanishes into the tangled figs and vines of the forest. Sometimes I hear a terrible commotion – hysterical chattering from the dassies or screams from the baboons. The mamba’s strike is fleet and deadly.

A long time ago my father warned my older sister and me of serpents. He stood above us, silhouetted against the bright sky, as we set out to fetch water from the stream near our homestead. He said we should look where our feet fall on the path because the sluggish puff adder warms itself there. He told us to strike with a heavy stick the trunk of the whitewood trees we loved to climb so as to frighten off the charcoal and amber-banded coral snake or the emerald-green boomslang, both as slender and as quick as whips.

‘What about mambas, papa?’ I asked.

He turned away. He never answered. My sister put her lips, soft, to my ear and whispered, ‘Pray that you never see one.’

Lobengula comes to me in secret now, for he is King, and I am long dead by the mamba - or so the story is told. If I were to tell him of the snake he would send a young warrior to throw an axe to sever its head while it suns itself high on the rock. There would be many volunteers impatient to prove their fearlessness. But I dare not speak of it for some say that stories hold not only memory, but prophesy.

We will not be disturbed, Lobengula and I, because at the time when the light of day drains fast away through the cracks in the rocks, I go to the place shown me long ago by old Lwazi, the sorcerer, and sing songs of my childhood in a low voice that journeys through the hills. The monkeys whimper and huddle together in the mukwakwa trees and no man will come near our valley for dread. Lobengula tells me that it is said that some hear my name although I do not sing it. They hear ‘Serra, Serra, Serra.’ He says the Amandebele warriors weep to hear it.

I make a fire for Lobengula with grass kindling and scented marula wood and place oil-seed candles in front of the rocks whose faces bear feathery symbols of dreams in ochre. Lobengula brings meat and beer and I grill corn and make a relish from herbs and roots gathered from the forest. While we wait for the meat to cook, we nibble roasted mopane caterpillars. Their nutty flavour whets our appetites. Above us, the trees are pricked with light from the iridescent eyes of thousands of tiny night spiders.

Our oily fingers glisten in the warm glow of the fire as we eat and Lobengula talks freely of affairs of state. He wearies of the grovelling supplicants worming their way across the compound in the King’s kraal shouting, ‘Oh bull elephant that shakes the ground,’ or ‘Lord of Thunder and Stabber of the Skies,’ but he speaks proudly of his twenty five thousand warriors who parade in ostrich-feather headdresses and goat skin gaiters and arm bands while he sits with his many wives, wearing his crown: a single feather from the blue crane.

I listen and give Lobengula encouragement and counsel. I ask after those I know and coax him to tell me any gossip and news he can bring to mind. I do not ask how or when my exile will end. That is a riddle that even the King cannot answer.

When we have become merry with beer, we tell each other tales of when our love was young. I play music, plucking at my thumb piano and humming tunes that I must have learnt on my mother’s knee for they are not known to Lobengula’s people. Lobengula smiles as I play and watches the blush of the embers. Then we sit silent under the stars, chewing the root of the isinga tree (which heightens desire), listening to the calls of the owl monkeys and the nightjars. I massage his shoulders with oil before drawing around us a fine blue cloth. We lie together on a kaross under the stars.

Later, as he sleeps, I remember how our love purged my heart of grief and led me to betray my own people so that I can never return but must live alone in these hills. As for the remembrance of my kin, I recall my father but only in his warning, and my mother and brothers as if in a tale told by an old woman. But I remember well my older sister although I was a young girl when she died.

We were snatched, my sister and I, by Mzilikazi’s indunas as they raided, conquering all the tribes far south of the Limpopo. My sister pined with a terrible force for our father, mother and our brothers, all dead by the assegai. She was almost a young woman when we were taken and the indunas did to her as was their due.

After, the light went from her eyes and she refused to eat. Then she refused to walk, until the indunas left her beside a baobab tree to die. I threw myself on her and held to her with my child’s hands but I was torn from her by my captors who wished to hurry north to escape the battalions of Tshaka. I cried for many days but the indunas treated me gently, regretting, I think, the death of my sister.

For weeks we passed through a hot thirsty country with dry-leaved trees. Some perished for lack of water and grain. I was given over to the care of one of Mzilikazi’s wives. She treated me indifferently but her youngest son, Lobengula, of my age, walked beside me silently, while his brothers and cousins teased and prodded me.

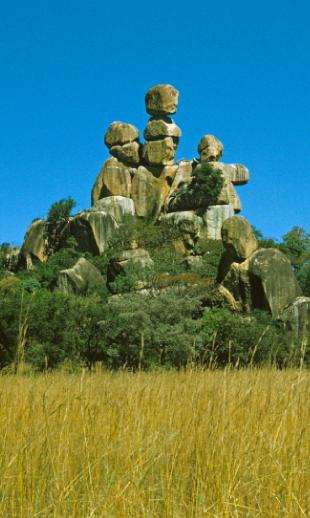

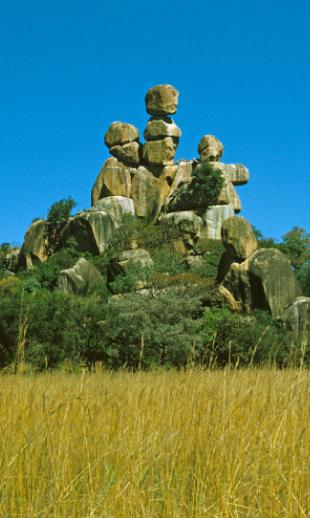

We crossed the Limpopo River losing cattle and slaves to crocodiles but I was borne high in a warrior’s arms as if I were some precious treasure. North of the river we followed in the path of Mzilikazi and his men until we came to great domes of rock which rose like bald heads from jade-green valleys. The haughty impi became quiet, afraid to enter the hills. Protective fences of hook thorn were cut and the warriors slept close to the fires at night. In daylight they satisfied their lust for war by raiding to the west and to the east, returning with cattle and women but they did not enter the hills. It was not ambush they feared - although no place is as fit for surprising an enemy - but the spirits, their mediums, and the God, Mlimu, who lives in the hills; they feared the long-tailed isitukwani that appear in red ochre on the faces of the rocks during the day but at night fly as quiet as bats to pluck the heads off sleeping men. They feared most the voices in the night that echoed from rock to rock.

We waited many days in sight of the hills while the elders called an indaba to come to a decision on whether to raid and subjugate the Makalanga people living there. They were few in number, unarmed, and concerned themselves with smelting iron and practicing sorcery. All night the elders deliberated until, at dawn, out of the grey light came a dark form, a sorcerer, walking alone out of the hills and into the circle of men. His name was Lwazi, which means ‘shepherd,’ and he announced that the sorcerers of the Matobo hills would act as spiritual advisors to the great Amandebele nation. They would be their priests and guides and would fashion their weapons. The elders discussed the proposal for two days. When Lwazi returned they had made their decision.

Lwazi led us through the hills until we came to a plain where cattle could be grazed and our nation could settle. Mzilikazi built a mighty kraal surrounded by high palisades of termite-proof wood in a place named Bulawayo. He set out compounds for tanners, metal smiths, weavers of rope, drum and plough makers and workers of wood. The brewery and the huts of the King’s wives abutted the King’s sanctuary.

I grew up in the great kraal with Lobengula. I wore a necklace and an apron of black and red seedpods, becoming skilled in many arts: making perfumed pomades from the seeds of the umsikila tree; painting patterns in ochre, charcoal and clay on the walls of our dwellings whose meanings only the women knew; singing and dancing in the grand parades. When we were still young, Lobengula and I played in the fields making snares for little birds with the sticky white sap of the Euphorbia tree. We held them close to feel their soft trembling breasts on our cheeks, before releasing them to catch the wind of their wings in our hands. Once, after this game, for some lost reason, I wept. Perhaps I remembered my sister.

Mzilikazi was often away from the kraal raiding far with a five thousand strong impi, their homecoming marked by the beating of the royal drums and ululations of the women. One dry season he did not return and rumours reached us that his force had been annihilated north of the Zambezi River. The remaining warriors became restive and skirmishes broke out amongst the men. To prevent insurrection, the elders conferred and appointed Lobengula’s brother to take Mzilikazi’s place as King.

Before the first smell of rain, I saw Mzilikazi and his exhausted men returning in haze and dust. Fear swept the kraal like a hot wind. Women called in their children, men cowered in the shade of the trees, dogs slunk away. His fury at being usurped was as of a wounded leopard. His sorcerers sniffed out traitors, settled old scores, killed any who might threaten the King’s throne again. Many were thrown from precipices or impaled on stakes.

We fled to the hills, Lobengula and I, lest a finger was pointed at us. We wandered deep amongst the high rocks until Lwazi came to us and led us down hidden watercourses, between tight clefts of rock, through latticed tunnels of fig roots and under curtains of vines, until we came to the foot of a great bald head of granite where we could live in secret. From then on Lwazi came to us often and Lobengula and he became friends, the older man teaching the younger wisdom and cunning in dealing with men. They hunted together and talked late under the night sky.

It was during this first exile that I saw the raiding party. I was gathering thatching far from our dwelling when I heard the hissing of the high grass and the hot exhalations of their horses as they found their way up the valley. I sank to my knees and watched them pass, seeing only the riders’ green-felt wide-brimmed hats stained with soil and spotted with blood. I saw their hair, as fair as the dry thatch grass, and as fair as my own. I heard their quietened voices. My bladder gave way. They spoke the language of my childhood whose words were now only known to me in song. They were the people of my birth.

I struggled to my feet when they had passed and opened my mouth to cry out to them, finding the tongue of my infancy, ‘My name is Sarah. I am Sarah,’ but my voice died in my throat. There was a young Amandebele woman tied down to the back of one of their horses. Her head was turned towards me and I saw she was numb with fear. I dropped again to my knees and retched, holding my belly. I was heavy with child by Lobengula. Love must choose.

I hurried, hot, clammy, faint, over and around the rocks, taking every secret way, arms plucked by waitabit thorns, toes stubbing on granite, until I came back to Lobengula. I sank at his feet as he came to hold me. ‘There are raiders coming, my love,’ I said. ‘I’ve seen them at the Maleme River.’

Lobengula left me and ran for a day to reach Bulawayo to warn Mzilikazi.

I heard that the indunas trapped the raiders in a ravine. Their felt hats were used to soften the wooden pillows that the warriors carried on their journeys.

I bled that night. My child, a boy, was still born. I wailed, although there were none but the night creatures to hear it, and buried him before the first light of dawn in a place only the moon saw. It seemed to me an omen; a portent that there would be no coming together of our peoples; that the time when our blood would blend in union, not war, was far, far away.

For many days I lay on a high rock watching for Lobengula’s return, waiting to know if he had pleased the King or had been executed. But Lwazi came first with news that Lobengula had found great favour with the King for his warning; that the King had welcomed him as a lost son and had named him as his successor.

I hurried, laughing and weeping when I saw Lobengula from afar but I stood still to receive him when he neared me on the path. He walked strong and proud in his new skins and his anklets of leopard’s teeth. I told him of our loss in a quiet voice and with the dignity that befits the consort of a prince. Then I washed the blood from his assegai; the blood of my own people.

We left our secret dwelling and returned together to the great kraal. I became Lobengula’s favoured wife and was honoured by the people when my part in the repulsion of the raiders became known. Many rains came and went. Our granaries overflowed and our cattle grew fat. I bathed in the Queens’ Pool and was attended by my maids. My one sorrow was that I remained barren although Lobengula sought for me the remedies of the greatest medicine men between the Limpopo and the Zambezi.

But when it appeared that Mzilikazi’s strength was fading, the wives of Zulu blood whispered against me. Lobengula was to be made King and so should not have a foreign wife. The murmurings grew until Lobengula took counsel from old Lwazi. In a night so dark that even the dogs were silent, Lwazi led me away into the Matobo hills, finding again this hidden place. Then he returned to Bulawayo and told the elders that I had died by the mamba while gathering wood. The women wailed. The men stamped their feet and beat their shields with their knobkerries.

So began my second exile in which I must live alone, following the rhythms of the seasons, gathering grains and fruits, humming the songs of my infancy, and listening for the footfall of the King.

I have not told Lobengula that I have seen the mamba. He left this morning, walking to the head of the valley where his most trusted indunas wait to escort him back to Bulawayo. I feel an unsettled breeze from the south and do not know how many seasons my life here will continue. Old Lwazi tells me that there are white men coming. ‘Many, many,’ he says. He tells me that they are hungry for land and for gold. This I believe and when they come I will run again to warn Lobengula so that he can send out his warriors. I will run over the summit of the dome of rock above my dwelling for that is the quickest way back to Bulawayo. Let the old women do their worst to me. I no longer fear them. But lately I have not slept for what old Lwazi told me. His spies say they have seen a party of white men crossing the Limpopo, and that they ride with a woman. The boys in their camp say that she seeks her younger sister, snatched away from her in her youth

I am dead by the black mamba - so says the story already told - but my sister does not know it. I pray that when I see the raiders in their strange hats that I see no woman riding with them, lest I have to choose: to run out across the vlei to greet my sister, or to hasten to warn Lobengula, crossing over the rock above my dwelling

Copyright © Andrew JH Sharp 2013. This short story may not be reproduced without the consent of the author.