OTHER EDENS

Uganda

The Victorian explorer Speke first heard about Uganda from the Arabs on the East African coast at a time when European maps of central Africa were drawn depicting elephants instead of landmarks for want of accurate information. Of this Kingdom of Uganda, wrote Speke, we hear from everybody a rapturous account. It swarms with people who cultivate coffee and all the common grains, and have large flocks and herds.

Travellers have been similarly enchanted ever since. Richard Dowden’s words in his book Africa, Altered States, Ordinary Miracles are particularly apt for Uganda: visitors … suddenly find themselves cracked open. They lose inhibitions, feel more alive, more themselves, and they begin to understand why, until then they only half lived. ... to risk a huge generalisation: amid our wasteful wealth and time-pressed lives we have lost human values that abound in Africa.

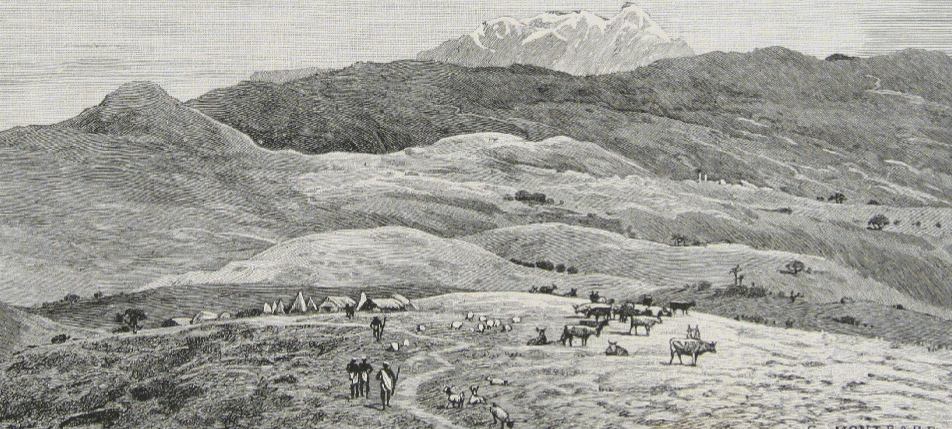

Lunae Montes

They dropped down a forested escarpment of ironwood, thick with leaf and vine and moving with feathered and furred creatures, into a geological playground… Ahead, the sun had been swallowed whole by the clouds of the Rwenzori massif.

My characters Stanley, Felice and Michael are descending the precipitous road into the Albertine Rift Valley in western Uganda. For Michael the dramatic landscape holds the promise of entering an Eden with the beautiful Felice but, even without romantic love, the area is enchanting and dramatic.

The first European explorers to report their discovery of the snow-capped Rwenzori mountains in the Albertine Rift associated them with the tales by ancient Arab travelers and Greek geographers of the Lunae Montes whose melting snows formed the headwaters of the Nile. Although modern geographers place the headwaters further south in the hills of western Tanzania, the heavy precipitation that falls on the Rwenzoris from the water-laden clouds of the Congo basin to their west contributes significantly to the Nile’s flow.

Gigantic volcanic explosions rocked the rift just a few thousand years ago leaving the valley floor pocked with craters. On a recent trip to Uganda I saw two ancient male buffalos living out their retirement in the lush basin of one of these craters, whose sides seemed too steep to permit escape but also too steep for a lion to bother with the descent.

Beyond the mountains, reported the survivors, spread a limitless sea that evoked a deep yearning, a joy, an abandonment, so that men would throw themselves into the water …

Those standing on the Rwenzori mountains nowadays, looking west, see the edge of the second largest forest in the world stretching towards the Atlantic over a thousand miles away. The legend of a great sea seems fanciful, but geology has revealed that it is not, although no human eyes would have seen it, for about 12 million years ago a giant lake formed to the west of the Rwenzoris as the rift floor sunk and the west-flowing rivers flowed in. Tectonic forces further fashioned the rift, splitting Lake Obweruka in two to form the present day lakes Albert and Edward – with a smaller lake, George, beside Edward. All named, of course, by those energetic Victorian explorers.

If you’re travelling to Uganda make sure you read Andrew Robert's book Uganda’s Great Rift Valley, an entertaining and informative guide to this historically fascinating and scenically breathtaking region.